UNCLE TOM REVISITED: Rescuing the Real Character from the Caricature -- Today the phrase "Uncle Tom" evokes a powerfully negative image in American society. It depicts a weak, subservient, cringing black man who betrays his race and its struggle for liberation. David Reynolds, an English professor in the Graduate School of the City University of New York (CUNY), returns to the original "Uncle Tom's Cabin" to reveal that the character Harriet Beecher Stowe described in her 1852 novel is wholly opposite of the caricature we now imagine. His article explores how Stowe's Uncle Tom evolved into our contemporary negative image of Uncle Tom.

=========================

PERSONAL NOTE: Having read "Uncle Tom's Cabin" years ago I have always viewed Uncle Tom as a compassionate man who made the best of a challenging situation. A transformative figure who died to save others. Because that, I have always wondered why and how Uncle Tom became such passive, subservient figure. And how many who use this term have actually read the book?

========================

The novelist Harriet Beecher Stowe, born 200 years ago, was an unlikely fomenter of wars. Diminutive and dreamy-eyed, she was a harried housewife with six children who suffered various obscure illnesses, worsened by her persistent hypochondria. And yet, driven by a passionate hatred of slavery, she found time to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which became the most influential novel in American history and a catalyst for radical change both at home and abroad.

Today, of course, the book has a decidedly different reputation, thanks to the popular image of its titular character, Uncle Tom — a name that has become a byword for a spineless sell-out, a black man who betrays his race.

But this view is egregiously inaccurate: Uncle Tom was physically strong and morally courageous, an inspiration for blacks and other oppressed people worldwide. In other words, Uncle Tom was anything but an “Uncle Tom.”

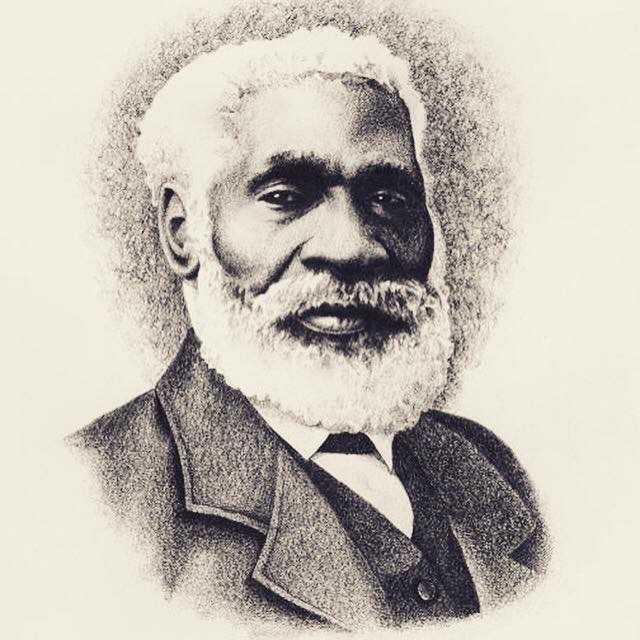

Stowe describes Tom as “a large, broad-chested, powerfully-made man” with a “self-respecting and dignified” look that indicates “grave and steady good sense.” A man around forty with a wife and three children, he is notable precisely because he does not betray fellow enslaved blacks. He turns down an opportunity to escape from his Kentucky plantation because he doesn’t want to put his fellow slaves in danger of being sold or punished.

Later on, he endures a terrible whipping at the hands of the cruel slaveowner Simon Legree because he refuses to reveal where two enslaved women are hiding. We are told that Tom “felt strong in God to meet death, rather than betray the helpless.” Legree regards Tom as a brash troublemaker who is despicable because he is unflinching: “Had not this man braved him,--steadily, powerfully, resistlessly,--ever since he bought him?” After the Civil War a group of ex-slaves to whom the novel was read aloud declared that few enslaved blacks would have dared to resist their master as determinedly as Tom does.

Moreover, in a day when blacks were widely regarded by whites as subhuman, lustful, or comically irresponsible, Uncle Tom’s Cabin demonstrated that they were capable of the full range of feelings—loyalty, friendship, sorrow, pity, and religious devotion. On every page, Stowe made a crystal-clear point: blacks were human, and to enslave them was evil.

That’s why in the mid-nineteenth century Southerners savagely attacked “Uncle Tom Cabin” as a dangerously radical book. A Southern political cartoon depicted Stowe in hell, surrounded by demons and holding a book titled Uncle Tom’s Cabin. I Love the Blacks. Previously, Southerners had thought it unnecessary to write lengthy defenses of slavery, which was seen as a natural part of the American system.

But Uncle Tom’s Cabin made its point so powerfully and with such popular success—it sold over 300,000 copies in America and around 1.5 million abroad in a year--that it provoked numerous attacks in Southern poems, reviews, articles, and books. Thirty novels were written in reply to “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” In these so-called anti-Tom novels, slavery was presented as a wonderful institution, sanctioned by the Bible and by the laws of the land, that provided ignorant African savages with shelter, food, and religious instruction.

Meanwhile, Stowe’s novel greatly strengthened antislavery sentiment in the North. For the first time, Northerners felt the horrors of slavery on their nerve endings. Many antislavery reformers jumped on the Uncle Tom juggernaut. Previously, the antislavery movement had been divided between small, conflicting groups that were widely unpopular. Uncle Tom’s Cabin was a force for unity and cohesion among these fragmented groups. Stowe was overjoyed by the embrace of her novel by different antislavery factions...