Granbury’s Greatest Newspaperman

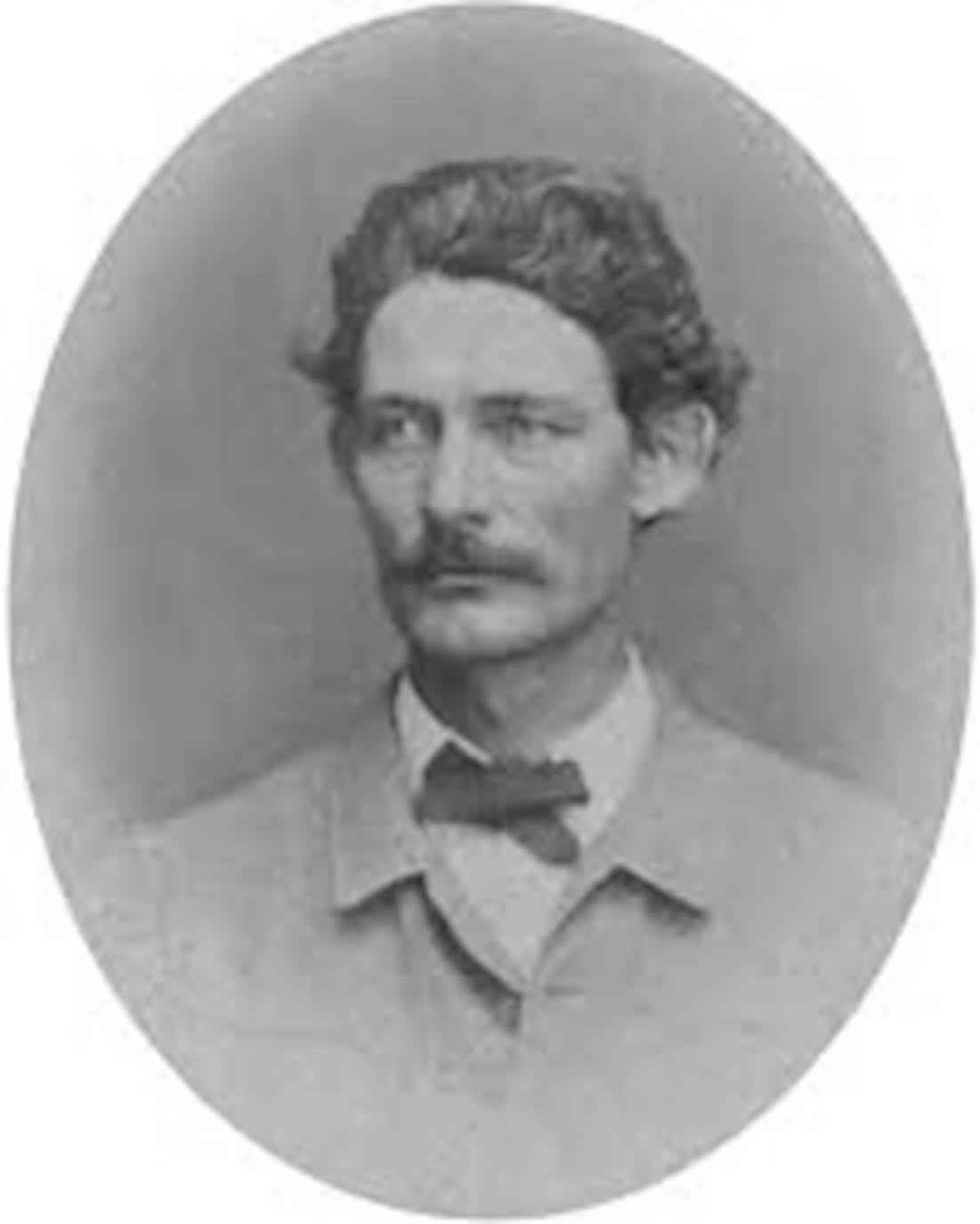

It was a cold day in January 1938. The octogenarian pulled on his overcoat, put on his hat, and retrieved his cane. He left the upstairs office and walked down the flight of stairs better than most 81-year-olds. Reaching the street, he never saw what hit him. Mrs. A. D. Smith could not stop her car in time. Ashley Crockett lay in the street. Everyone knew the legendary newspaper editor and grandson of David Crockett. He was hurt, but Crockett did not want people making a fuss. Folks helped him return to his home, where he recovered. He was anxious to get back to the work that

meant so much to him.

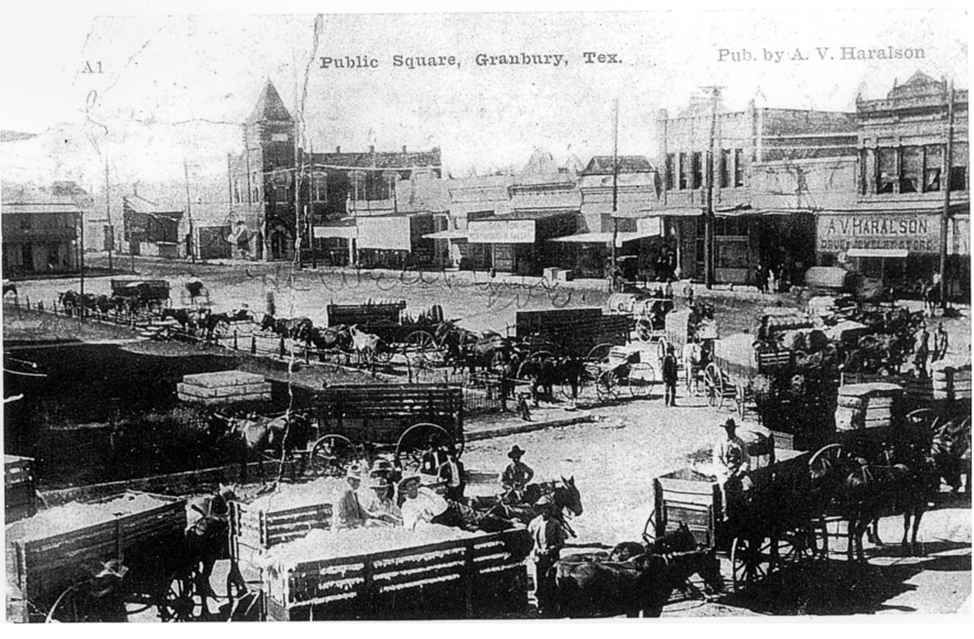

The young man walked confidently along the dusty street. He turned down the alley between two stores on the square. There he saw the side door stenciled with the words, ”Granbury Vidette.” A bell tinkled as he entered.

A moment later, Edward Garland emerged from the backroom in an ink-stained apron, vigorously wiping his blackened hands on a rag. He and W. L. Bond published Granbury’s first newspaper starting in November 1872.

”What can I do for you, son?” Garland asked.

”I’m Ashley Crockett, sir, ” the lad responded. “I want to be a newspaperman.” (I don't know if this is precisely what he said to Edward Garland, but I do that a few years later, he told the 1880 census taker his occupation was “newspaperman.”)

Ashley did not have much education since he lived all of his early life isolated on the Texas frontier. He was too frail for rigorous farm work. Due to a congenital disability, Crockett had sight in only one eye. Ashley remembered that at age 12, his father suggested that he go to Weatherford Trading Post and learn the printer’s trade from a man named Duke. Col. R. W. Duke started the paper just three years previously.Isaac Duke put Ashley to work as a printer’s “devil”, and entry-level job. Ashley recalled that he had no place to stay in Weatherford. Col. Duke gave him a buffalo robe and told him to sleep in a lean-to barn. ”I heard (horse thieves) at night, moving through the brush,” Ashley recalled. ”I remained breathlessly quiet, so they would not find me.”

Crockett was a fast learner and a conscientious worker. So enterprising was the young man that he bought the Vidette in 1883 and changed its name to the Granbury Graphic. In 1907 someone must have made Ashley an offer he couldn’t refuse. He sold the Granbury paper and moved to Glen Rose, where he worked on the local gazette. But after some years, he returned to Granbury. Crockett got a job at the Post Office.

During this time, Ashley married Anna Marie Walkup, 22, in Red River, Texas. Between 1898 and 1913, the Crocketts had four girls, Gladys, Elizabeth, Margetta, and Hellen. He had been married once previously to Onalda Hayes with whom he fathered a son, Chester, and a daughter, Virginia.

In 1919 Ashley bought back his old paper and renamed it the Granbury Tablet. He continued working on the Tablet until he retired due to poor eyesight in 1930.

Ashley Crockett, the one-eyed editor, worked for eighty years in the newspaper business in Granbury. The current paper, The Hood County News, is a direct descendant of Ashley Crockett’s publication.

Mr. Crockett lived to be 97 years old. He died in 1954. He was the oldest resident of Hood County at the time of his death. Anna Marie passed away in 1935. They are buried in Granbury City Cemetery.

Dr. David K. Barnett

Granbury History

Sources:

Granbury News, January 8, 1938.

“David Crockett’s Grandson Edits Hood County Paper, ” Fort Worth Star Telegram, December 7, 1937.

Hendricks, Kenneth, ”Remember the Crocketts.” Lecture transcribed by Tex Dendy, April 2008. Hood County Texas Genealogical Society.

Wharton, Clarence R., Texas Under Many Flags, Volume III. Clarence R. Wharton, Author, and Editor. 1930: The American Historical Society, Inc., Chicago & New York.