THE TREATY OF FALAISE - SCOTLAND & ENGLAND

1174 AD

The Treaty of Falaise was a forced written agreement made in December 1174 between the captive William I, King of Scots, and Henry II, King of England.

During the Revolt of 1173-1174, William joined the rebels and was captured at the Battle of Alnwick during an invasion of Northumbria. He was transported to Falaise in Normandy while Henry prosecuted the war against his sons and their allies. Left with little choice, William agreed to the Treaty and therefore England’s dominion over Scotland. For the first time, the relationship between the king of Scots and the king of England was to be set down in writing. The Treaty’s provisions affected the Scottish king, nobles, and clergy; their heirs; judicial proceedings, and transferred the castles of Roxburgh, Berwick, Jedburgh, Edinburgh, and Stirling over to English soldiers; in short, where previously the king of Scots was supreme, now England was the ultimate authority in Scotland.

During the next 15 years, William was forced to observe Henry's overlordship, such as needing to obtain permission from the English crown before putting down local uprisings. The humiliation for William caused domestic trouble for him in Scotland, and Henry’s authority extended as far as picking William’s bride.

The treaty was annulled in 1189 when Richard I, Henry's successor, was distracted by his interest in joining the Third Crusade, and William's offer of 10,000 marks sterling. More pre-disposed to William than his father, Richard drew up a new charter on 5 December 1189, known as the Quitclaim of Canterbury, that nullified the Treaty of Falaise in its entirety. This new written agreement restored Scottish sovereignty, reverting back to the previously vague and ill-defined personal traditions of fealty and homage between Scottish and English kings, rather than the direct subjugation that Henry demanded.

PICTURED: Chateau de Falaise, where William was held while the Treaty was negotiated.

SCOTLAND'S ANTONINE WALL

124 AD - The Roman Empire Arrives

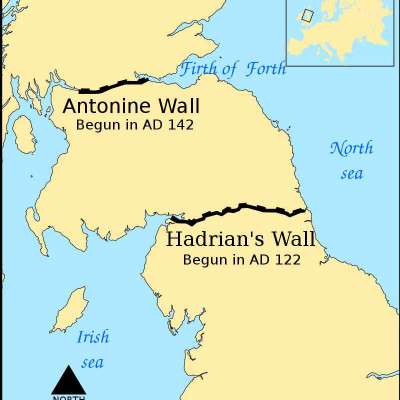

Scotland’s recorded history began with the arrival of the Roman Empire. Despite building two impressive fortifications – Hadrian’s Wall to defend the northern border, and the Antonine Wall across Central Scotland to advance it forward – the Romans never truly conquered Caledonia. Unable to defeat the Caledonians and Picts, the Romans eventually withdrew and over time retreated away from Britain. Much of the 60 km (37 miles) Antonine Wall survives and it was inscribed as a World Heritage Site, one of six in Scotland, since 2004.

The Antonine wall, often running through suburbs and sprawl, lacks the romance of its southern cousin (Hadrian's Wall)– and is less obviously well-preserved. (Built in turf rather than stone, the wall's surviving trace is most frequently its accompanying ditch. Though often it's no more than a dip in a field, it has many moments of beauty and drama at spots such as at Bar Hill and Rough Castle.)

SCOTLAND'S EARLIEST HISTORY

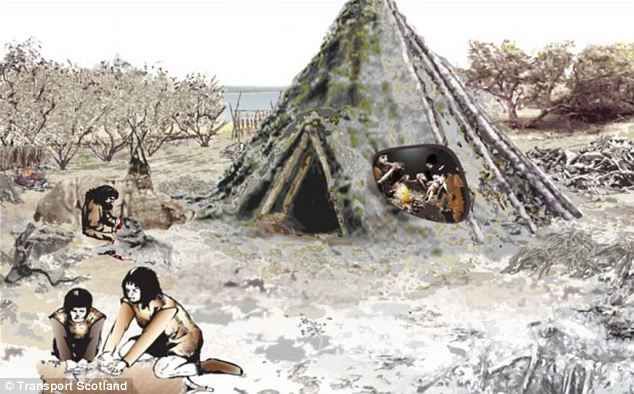

Archaeologists discover 10,000 year-old home - and reveal residents were partial to hazelnuts

A large oval pit measuring nearly seven metres and studded with post holes was all that remained standing of the home from the Mesolithic period. The dwelling was found in the path of the new Forth bridge and has been dated to around 8240 BC.

The holes would have held wooden posts supporting the walls and roof, which experts believe would have been covered with turf. Remains of several fireplace hearths were also discovered.

The ancient people who lived in the area were hunter gatherers and charred bone fragments on the site suggest they ate birds, fish, wild boar and possible deer. Large quantities of charred hazelnut shells were also found. The residents were among the first settlers in Scotland after the last glacial period (a time within an ice age marked by colder temperatures).

Archaeologists also recovered more than 1,000 flint artefacts including stone tools that would have been used for tasks including hunting, skinning and food processing.

Ed Bailey, Project Manager for Headland Archaeology, the company that carried out the works, said:

'The discovery of this previously unknown, and rare type of site has provided us with a unique opportunity to further develop our understanding of how early prehistoric people lived along the Forth.

'Specialist analysis of archaeological and paleo environmental evidence recovered in the field is ongoing. This will allow us to put the pieces together and build a detailed picture of Mesolithic lifestyle.'

Historic Scotland Senior Archaeologist, Rod McCullagh, said: 'This discovery and, especially, the information from the laboratory analyses adds valuable information to our understanding of a small but growing list of buildings erected by Scotland’s first settlers after the last glaciation, 10,000 year ago.

'The radiocarbon dates that have been taken from this site show it to be the oldest of its type found in Scotland which adds to its significance.'