What Did They Do with All the Manure in the Streets?

Global Warming. Acid Rain. Plastic in the ocean. Global Pandemic. Our news is filled with environmental emergencies. One of the first predicted eco-disasters was that dependence on the horse was going to bury cities in manure. London and New York each utilized over 200,000 horses for transportation. Each horse produced about two buckets of manure and one bucket of urine per day. At the current rate of growth, said the London Times, in 50 years, London and New York would each be buried under nine feet of horse dung and dead horses. (I’ll take global warming any day.)

Rural towns had fewer horses, but the output of manure and urine was the same. Walking along the sidewalks of many frontier towns, dust from dried manure filled the lungs and ammonia from horse urine stung the eyes. Many shopkeepers and other townsfolk in Texas communities kept manure forks and scoop shovels near at hand for removing unsightly deposits. It was simply a regular part of building maintenance -- just as mowing a lawn is today.

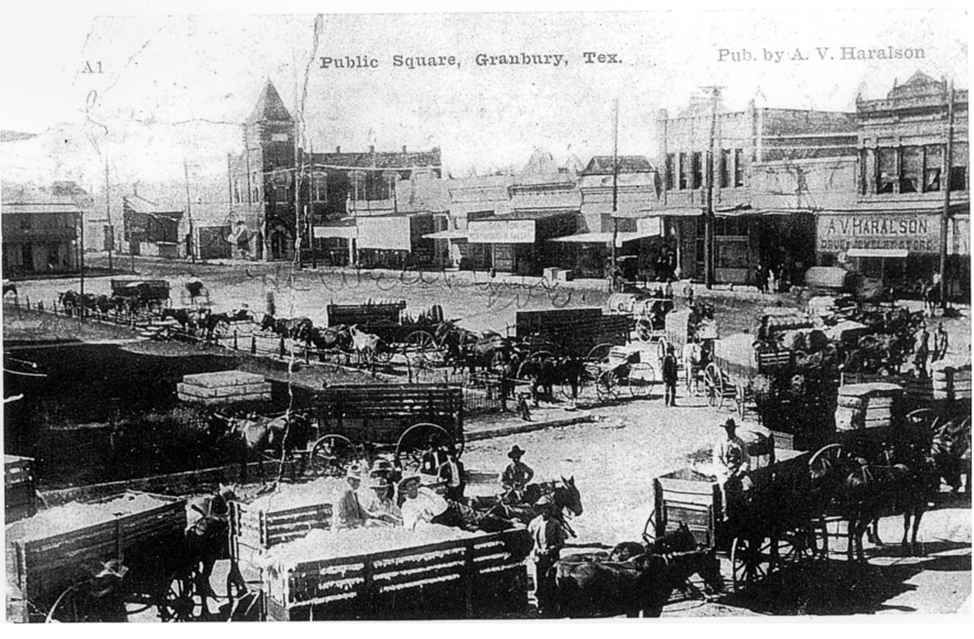

If there ever was a problem with horse manure in Granbury, none of the newspapers that have survived wrote about it. When I look closely at those old-time photos of Granbury street scenes (like that above), I don't see a lot of droppings.

So, what I want to know is, who kept Granbury's streets clean? And what did those people do with all the manure? In addition to horses, there were mules and dogs and cats, and even human waste was thrown into alleys and thoroughfares of the frontier town.

As to who kept the streets free of muck, most Texas towns did not have the budget for road crews. If the jail had inmates, prisoners could earn time off their sentences for cleaning streets. If no one was in lock up, the sheriff might hire an adolescent for 10 cents an hour to shovel manure into a wagon or wheelbarrow.

As to where they dumped the manure, I can think of two places. One might have been nearby farms which needed fertilizer for their crops. Farmers deposited dung in a harvested field to dry and later be plowed into the soil before planting season. Another solution for towns built on major rivers was to dump the waste in the river and let it wash downstream. Our ideas of water conservation never occured to the frontier mind. Pioneers believed that natural resources were unlimited. Pollution only became a concern after World War 2 when citizens began to demand cleaner water. In Northern Ohio, for example, the Cuyahoga River was so polluted, it routinely caught fire as late as 1969.

The only place in Granbury where manure may have been a public nuisance was in the courthouse square on market day, like that depicted in the photo above. In this case, it would have most likely been the job of Andy Zweiffel to clean up after the horses. Zweiffel was the courthouse janitor.

Andrew Zweifel was born in Switzerland in 1853 and came to Texas when he was 14 years old. He married Sarah E. Smith in 1882 in Granbury. Of the eight children born to the couple, only three survived to adulthood. Andy died in 1912; Sarah in 1936. Andy’s death certificate said he died from ”enemia” (sp) complicated by paralysis. Interestingly, his son, Henry, who provided the family information for the death certificate, listed his father’s occupation as stonemason. The janitor job may have been necessary in later life when he could no longer work in the building trade.

So, before sewers, septic systems, waste treatment plants, and trash collection, Granbury’s first sanitation department was one unsung hero who traded his mallet for a mop, and his chisel for a shovel.

David K. Barnett

Granbury History

Sources:

Flowers, Erik, quoted in Muslim, Peter, ”Pollution – Why we replaced horses with automobiles, ” greenprojectmanagement.com

Trimbull, Marshall, ”Who was in Charge of Keeping Western Streets Clean?” True West: History of the American Frontier website, July 16, 2019.